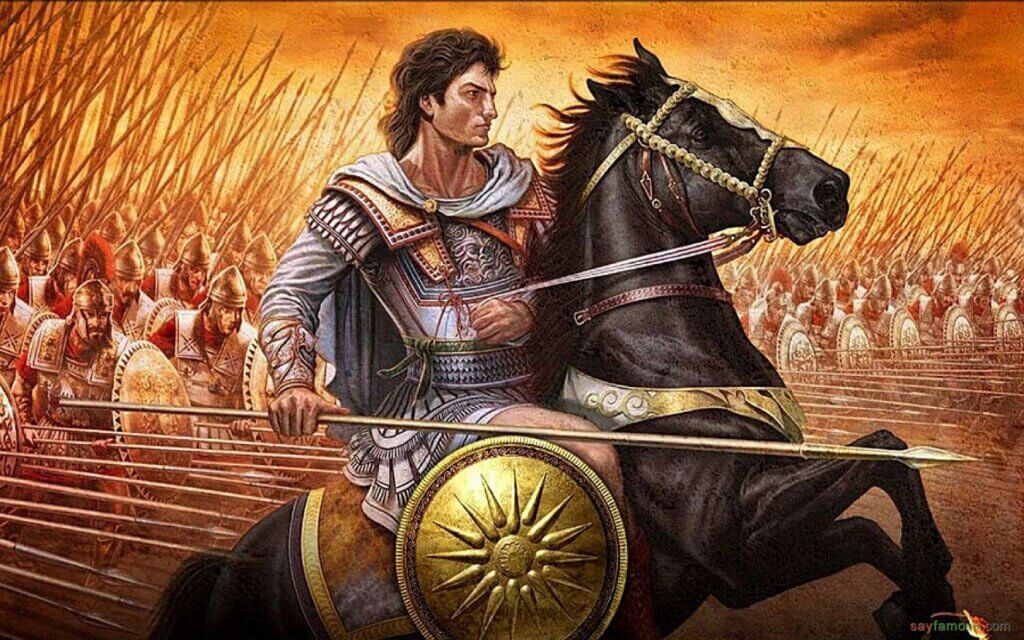

In 331 B.C., Alexander the Great and Darius III of Persia fought at the Battle of Gaugamela. It is also known as the Battle of Arbela, and it was a very important victory for the Macedonians that helped bring down the Persian Empire. The conflict took place in Gaugamela, a town on the banks of the river Bumodus whose name roughly translates to “The Camel’s House.” According to Urbano Monti’s globe map, the region is now known as modern-day Erbil, Iraq. Alexander’s army was vastly outnumbered, and according to contemporary historians, “the odds were sufficient to give the most seasoned warrior pause.” Alexander’s army prevailed against overwhelming odds by using better tactics and employing light infantry battalions intelligently. It was a major victory for the League of Corinth, which resulted in the collapse of the Achaemenid Empire and the death of Darius III.

Let’s dive deep into one of the greatest battles of Alexander’s life

Location

Darius chose a flat, wide plain where he could spread out his larger army. He didn’t want to be stuck in a small battlefield like he was two years earlier at Issus, where he couldn’t use his huge army well. Before the battle, Darius had his soldiers level the ground so that his 200 war-chariots could move easily. But this wasn’t important. Alexander couldn’t hide on the ground because there weren’t many hills or bodies of water, and the fall weather was dry and pleasant (see his Limes Report, pp. 127–1)

Background

After the Battle of Issus, Alexander ruled for two years along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea and in Egypt. As he moved from Syria into the heart of the Persian empire, he had no trouble crossing the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. Before the battle, Darius tried to make peace with Alexander by offering to give him half of the Persian Empire if Alexander stopped his invasion of Persia. Alexander turned down Darius’s offer outright. One of Alexander’s generals, Parmenion, said that he would gladly accept the tempting offer if he were Alexander. Alexander said, “Likewise, if I were Parmenion.”

The time of attack

On the night before the battle, Alexander’s generals, especially Parmenion, suggested a surprise attack at night to make up for the Persians’ huge number. Alexander said he wouldn’t do this, saying he wouldn’t “steal his triumph.” This was either a stroke of luck or a stroke of genius, because Darius, who thought Alexander would attack at night, kept his army awake and on guard all night, while Alexander’s army was left alone to sleep. Alexander slept too long the next day. When his worried generals woke him up, he said in a matter-of-fact way that the battle was already over.

Total size of the Persian army

Other ancient Greek historians think the main Persian army had between 200,000 and 300,000 warriors. However, some modern researchers think it had no more than 50,000 warriors because it would have been hard to get more than 50,000 warriors into battle at the time. The Persian army may have had more than 100,000 men, though. One estimate says there were 25,000 peltasts, 10,000 Immortals, 2,000 Greek hoplites, 1,000 Bactrians, 40,000 cavalry, 200 scythed chariots, and 15 war elephants. Hans Delbrück puts the number of Persian cavalry at 120,000. .[10]

Welman says there are 90,000 people, Delbrück says there are 52,000, Engels says there are no more than 100,000, and Green says there are no more than 100,000.

The fight

How did the fight start?

Alexander opened the battle by ordering his men to advance in phalanx formation into the heart of the opposing line. To get the Persian cavalry to attack, the Macedonians moved toward them with their wings folded back at a 45-degree angle. While the phalanxes fought the Persian soldiers, Darius sent most of his cavalry and some of his regular army to attack Parmenion’s left flank.

Alexander used a strategy in the fight that has only been used a few times since. Alexander rode to the right flank with the help of his Companion Cavalry while his soldiers fought Persian forces in the middle. His goal was to get as many of the Persian cavalrymen as possible to move to the sides so that a hole could be made in the other side’s line. Darius could then be hit hard. Alexander had to act quickly and with almost perfect timing and manoeuvring. Alexander would force Darius to attack, even though Darius didn’t want to be the first to attack after what happened at Issus against a formation like Alexander’s.

Rat-trap technique

Now, Darius sent out his chariots, but some of them were stopped by the Agrianians (javelin throwers). Legend has it that the Greek army planned a new way to beat these deadly chariots if they came racing into their ranks: the first lines would move apart to make a space. The horse wouldn’t rush into the spears of the front lines. Instead, it would go into the “mousetrap,” where the spears of the back ranks would stop it. Then the charioteers and their horses could be killed whenever they wanted.

Alexander’s decisive assault

As the Persians got closer and closer to the sides of the Greeks as they attacked, Alexander slowly moved his back line back. Alexander sent his allies away and got ready for the final attack. He set up his troops in a huge wedge shape and led the attack himself. Behind them were the guards brigade and any phalanx battalions he could pull out of the fight. There were more light soldiers here. Alexander led most of his cavalry away from the battlefield, parallel to Darius’ front lines. In response, Darius sent his cavalry to the front lines to stop Alexander’s army. Alexander hid a force of peltasts (light infantry with slings, javelins, and shortbows) behind his horsemen. He then slowly moved his force toward the Persian army in an angle until a gap opened between Bessus’s left and Darius’s centre. He then sent his cavalry to drive down the Persian line in a wedge shape. The peltasts attacked the cavalry at the same time to keep them from going back to face Alexander’s charging cavalry. The Persian infantry in the middle was still fighting with the phalanxes, so no one could stop Alexander’s advance.

Plank on the left

Alexander might have been after Darius at this time. But Parmenion, who was on the left, sent him frantic messages (an occurrence that Callisthenes and others would later exploit to defame Parmenion). Alexander had to decide if he should go after Darius and try to kill him, which would end the war in one blow but could cost him his army, or if he should retreat to the left flank to help Parmenion and save his troops, letting Darius escape into the nearby mountains. He helped Parmenion and then went with Darius.

As the left side of the Greek line held, a gap opened up between it and the middle. The Persian and Indian cavalry charged through, with Darius in the middle. Instead of taking the phalanx or Parmenion in the back, they went to the camp to steal from it. They also tried to save Queen Mother Sisygambis, but she didn’t want to come with them.

When the centre and Darius fell apart, Mazaeus and Bessus both started to pull back their troops. On the left, however, where Bessus was, the Persians quickly fell apart when Thessalian and other cavalry forces charged their fleeing opponent.

Most glorious battle of Alexander’s life

Conclusion: Consequences

After the battle, Alexander and his guards went after Darius while Parmenion picked up the Persian baggage train. At Issus, a lot of booty was taken, including 4,000 talents, the king’s personal chariot and bow, and the war elephants. It was one of Alexander’s greatest victories, and the Persians lost badly.

Darius and a small group of his soldiers were able to get away without getting hurt. He was caught by the Bactrian cavalry and Bessus.

Pingback: When Alexander Faced a Mutiny From His Own Soldiers